На нашем сайте вы можете читать онлайн «Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.)». Эта электронная книга доступна бесплатно и представляет собой целую полную версию без сокращений. Кроме того, доступна возможность слушать аудиокнигу, скачать её через торрент в формате fb2 или ознакомиться с кратким содержанием. Жанр книги — Серьезное чтение, Cтихи, поэзия, Стихи и поэзия. Кроме того, ниже доступно описание произведения, предисловие и отзывы читателей. Регулярные обновления библиотеки и улучшения функционала делают наше сообщество идеальным местом для любителей книг.

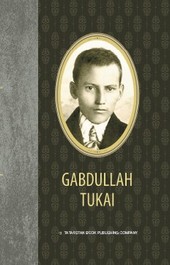

Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.)

Автор

Дата выхода

14 марта 2023

Краткое содержание книги Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.), аннотация автора и описание

Прежде чем читать книгу целиком, ознакомьтесь с предисловием, аннотацией, описанием или кратким содержанием к произведению Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.). Предисловие указано в том виде, в котором его написал автор (Gabdullah Tukai) в своем труде. Если нужная информация отсутствует, оставьте комментарий, и мы постараемся найти её для вас. Обратите внимание: Читатели могут делиться своими отзывами и обсуждениями, что поможет вам глубже понять книгу. Не забудьте и вы оставить свое впечатие о книге в комментариях внизу страницы.

Описание книги

Each and every nation of the world has its national poet who succeeds in truly, magnificently, powerfully and often painfully expressing the beauty of its heart and soul. Such poets are the resounding presence of their respective nations in the Divine silence of the Universe.

Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.) читать онлайн полную книгу - весь текст целиком бесплатно

Перед вами текст книги, разбитый на страницы для удобства чтения. Благодаря системе сохранения последней прочитанной страницы, вы можете бесплатно читать онлайн книгу Selected Poetry / Избранное (англ.) без необходимости искать место, на котором остановились. А еще, у нас можно настроить шрифт и фон для комфортного чтения. Наслаждайтесь любимыми книгами в любое время и в любом месте.

Текст книги

For instance, when the clothes I brought with me from Kazan – my shirts, pants, ichigi and kyavushy boots, and my knee-length coat with pleats – became worn out, my father decided to give me the blue linen shirt and the tunic which used to belong to his son, who died a year before my arrival.

Mother resented this plan of his for a long time: «I can’t give away to a stranger the clothes that belonged to my son, which I keep as a memory!»

Father finally flared up: «Come on, don’t be so spiteful! Do you want the kid to walk around naked because it wasn’t you who gave birth to him?» – With these words, he grabbed the clothes almost by force and told me to put them on.

III

The harvest was over and autumn came. When the wheat was reaped, it was time to dig potatoes.

This time around, when potatoes were being gathered, I didn’t have a chance to run and play as I did during harvest time: I had to put the dug potatoes into sacks. I coped with the work quite well.

Although it was already getting cold in the autumn, I was barefoot. So to keep my feet a little warmer, I stuck them into the ground.

Once, when I was sitting with my feet in the ground and sorting the potatoes, lame Sazhida apa accidentally thrust the iron shovel right in this place.

The wound was deep, so I jumped up and cried a little where no one could see me. Then I sprinkled the wound with earth and went on working, but no matter how frozen my feet were, I didn’t stick them into the ground again.

(They will ask: «Why did you write that?» What for? I did because the wound was very painful and I still have a scar from it on my leg, that’s why I decided to write about it.)

In the meantime, the work in the field came to an end.

One evening my mother and father told me that early the next morning they would take me to the school of the mullah’s wife, abystai.

We got up at dawn, before sunrise, and had some tea.

When we entered the house, we found abystai, who was to be my teacher, sitting there with a rod in her hand. Around her were little girls my age, these made the majority, but there were older girls as well. Scattered among them, like a few peas in a bowl of wheat, were little boys like me.